FLARE-On 12 Writeups (Part 1)

9053 words | 43 minutes

Introduction

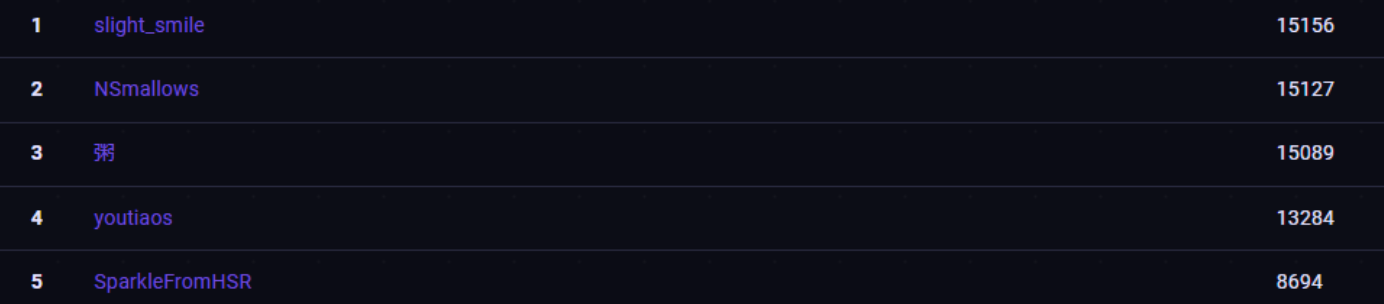

The FLARE-On Challenge is an annual reverse engineering CTF contest run by the Google Cloud FLARE Team/Mandiant that runs in autumn. This is my first time completing FLARE-On (given that I was too much of a busybee last year to commit to it) and I managed to complete it at 200th place globally (what a nice round number…) 196th, which is not as nice a number.

|

|---|

| Fig: Better late than never! |

As a player with who’s kinda rabak, these writeups will progressively get more and more… deranged and confusing as we go along. Without a doubt, there are far better ways to do a lot of the things I did, but hey. I did it my way.

Note: I’ll be splitting up my writeups into two parts as I feel the deobfuscation and ideas involved in Levels 7-9 deserve their own time and space. Also, time is a fleeting thing.

1 - Drill Baby Drill!

Effective Solve Time: 1 Minute

Realtime Solve Time: 2 Minutes

We are given a PyGame dist, with an EXE compiled version of the game and the original Python source code. The game itself is quite simple, you just go left and right and you can drill up and down, and the goal is to avoid hitting the boulders.

|

|---|

| Fig: Aw man. |

Solution

Hey, this is the first level in FLARE-On. Let’s just look at the source and not play the game.

1...

2def GenerateFlagText(sum):

3 key = sum >> 8

4 encoded = "\xd0\xc7\xdf\xdb\xd4\xd0\xd4\xdc\xe3\xdb\xd1\xcd\x9f\xb5\xa7\xa7\xa0\xac\xa3\xb4\x88\xaf\xa6\xaa\xbe\xa8\xe3\xa0\xbe\xff\xb1\xbc\xb9"

5 plaintext = []

6 for i in range(0, len(encoded)):

7 plaintext.append(chr(ord(encoded[i]) ^ (key+i)))

8 return ''.join(plaintext)

9...

Oh. It’s just an XOR. To show some respect to the challenge, we will at least determine what the key should be instead of bruteforcing the range. Knowing that the last letter of the flag is m from the end of @flare-on.com, we know the key is (0xb9 ^ ord('m')) - len(encoded)+1 == 180, so we just… plug that in.

1>>> GenerateFlagText(180<<8)

2'[email protected]'

3>>>

Wonderful.

2 - project_chimera

Effective Solve Time: 3 Minutes

Realtime Solve Time: 1 Hour

We’re given a Python file project_chimera.py, which just zlib decompresses and marshal loads some bytecode to run, which comprises the actual program. Here’s the program in full minus the fluff:

1import zlib

2import marshal

3

4encrypted_sequencer_data = b'x\x9cm\x96K\xcf\xe2\xe6...' # truncated for aesthetics

5print(f"Booting up {f"Project Chimera"} from Dr. Khem's journal...")

6sequencer_code = zlib.decompress(encrypted_sequencer_data)

7exec(marshal.loads(sequencer_code))

To solve, we need to disassemble the Python code object. However, this, of course, is version specific since there’s variations in Python bytecode. So besides guess and check, how do we determine the Python version? Well, something neat is that this source code has a nested f-string, in particular one with quotes inside another f-string. And according to StackOverflow:

|

|---|

| Fig: Thanks vro. |

This limits our search to Python versions 3.12 and above, and thankfully, Python 3.12 is the right version for this challenge! (I lost time here trying Python 3.13 and 3.14…)

$ uv venv --python 3.12

Using CPython 3.12.11

Creating virtual environment at: .venv

Activate with: source .venv/bin/activate

$ source .venv/bin/activate

$ python project_chimera.py

Booting up Project Chimera from Dr. Khem's journal...

--- Calibrating Genetic Sequencer ---

Decoding catalyst DNA strand...

Synthesizing Catalyst Serum...

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/mnt/d/Projects/ctfs/flareon/2025/2_-_project_chimera/project_chimera.py", line 33, in <module>

exec(marshal.loads(sequencer_code))

File "<genetic_sequencer>", line 22, in <module>

File "<catalyst_core>", line 4, in <module>

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'emoji'

Sick. I’m missing a bunch of modules necessary to run the program but honestly, since we’re able to just disassemble the code object, let’s just get ourselves some “source code”. We replace the exec in the initial script…

1import dis

2code_obj = marshal.loads(sequencer_code)

3dis.dis(code_obj)

and we can see the disassembly! WITH SYMBOLS!!! In the interest of brevity, I’ve truncated the output to keep the parts that matter.

...

LOAD_CONST 2 (b'c$|e+O>7&-6`m!Rz...')

STORE_NAME 4 (encoded_catalyst_strand)

PUSH_NULL

LOAD_NAME 5 (print)

LOAD_CONST 3 ('--- Calibrating Genetic Sequencer ---')

CALL 1

POP_TOP

PUSH_NULL

LOAD_NAME 5 (print)

LOAD_CONST 4 ('Decoding catalyst DNA strand...')

CALL 1

POP_TOP

PUSH_NULL

LOAD_NAME 0 (base64)

LOAD_ATTR 12 (b85decode)

LOAD_NAME 4 (encoded_catalyst_strand)

CALL 1

STORE_NAME 7 (compressed_catalyst)

PUSH_NULL

LOAD_NAME 1 (zlib)

LOAD_ATTR 16 (decompress)

LOAD_NAME 7 (compressed_catalyst)

CALL 1

STORE_NAME 9 (marshalled_genetic_code)

PUSH_NULL

LOAD_NAME 2 (marshal)

LOAD_ATTR 20 (loads)

LOAD_NAME 9 (marshalled_genetic_code)

CALL 1

STORE_NAME 11 (catalyst_code_object)

PUSH_NULL

LOAD_NAME 5 (print)

LOAD_CONST 5 ('Synthesizing Catalyst Serum...')

CALL 1

POP_TOP

PUSH_NULL

LOAD_NAME 3 (types)

LOAD_ATTR 24 (FunctionType)

LOAD_NAME 11 (catalyst_code_object)

PUSH_NULL

LOAD_NAME 13 (globals)

CALL 0

CALL 2

STORE_NAME 14 (catalyst_injection_function)

PUSH_NULL

LOAD_NAME 14 (catalyst_injection_function)

CALL 0

POP_TOP

RETURN_CONST 1 (None)

...

Well, we can just eyepower out that its taking another bytestring, performing base64.b85decode on it, then zlib.decompress and finally marshal.loads. So, we just do that in a separate file and disassemble that too:

1import zlib

2import marshal

3import dis

4import base64

5

6a = b'c$|e+O>7&-6`m...'

7code_obj = marshal.loads(zlib.decompress(base64.b85decode(a)))

8dis.dis(code_obj)

Once again, I’ll truncate the dis output because it’s mostly fluff.

...

LOAD_CONST 1 (b'm\x1b@I\x1dAoe@\x07ZF[BL\rN\n\x0cS')

STORE_FAST 0 (LEAD_RESEARCHER_SIGNATURE)

LOAD_CONST 2 (b'r2b-\r\x9e\xf2\x1fp\x185\x82\xcf\xfc\x90\x14\xf1O\xad#]\xf3\xe2\xc0L\xd0\xc1e\x0c\xea\xec\xae\x11b\xa7\x8c\xaa!\xa1\x9d\xc2\x90')

STORE_FAST 1 (ENCRYPTED_CHIMERA_FORMULA)

...

LOAD_GLOBAL 3 (NULL + os)

LOAD_ATTR 4 (getlogin)

CALL 0

LOAD_ATTR 7 (NULL|self + encode)

CALL 0

STORE_FAST 2 (current_user)

LOAD_GLOBAL 9 (NULL + bytes)

LOAD_CONST 5 (<code object <genexpr> at 0x71d2cc220b30, file "<catalyst_core>", line 25>)

MAKE_FUNCTION 0

LOAD_GLOBAL 11 (NULL + enumerate)

LOAD_FAST 2 (current_user)

CALL 1

GET_ITER

CALL 0

CALL 1

STORE_FAST 3 (user_signature)

...

So the first bit is a check that your “user signature” is equal to the LEAD_RESEARCHER_SIGNATURE after running it through getexpr, which is…

Disassembly of <code object <genexpr> at 0x71d2cc220b30, file "<catalyst_core>", line 25>:

25 0 RETURN_GENERATOR

2 POP_TOP

4 RESUME 0

6 LOAD_FAST 0 (.0)

>> 8 FOR_ITER 15 (to 42)

12 UNPACK_SEQUENCE 2

16 STORE_FAST 1 (i)

18 STORE_FAST 2 (c)

20 LOAD_FAST 2 (c)

22 LOAD_FAST 1 (i)

24 LOAD_CONST 0 (42)

26 BINARY_OP 0 (+)

30 BINARY_OP 12 (^)

34 YIELD_VALUE 1

36 RESUME 1

38 POP_TOP

40 JUMP_BACKWARD 17 (to 8)

>> 42 END_FOR

44 RETURN_CONST 1 (None)

>> 46 CALL_INTRINSIC_1 3 (INTRINSIC_STOPITERATION_ERROR)

48 RERAISE 1

ExceptionTable:

4 to 44 -> 46 [0] lasti

We can eyeball this expression, which seems to be performing c^(i+42) for each of the characters of the input. We can directly invert this:

>>> bytes([c^(i+42) for i, c in enumerate(b'm\x1b@I\x1dAoe@\x07ZF[BL\rN\n\x0cS')])

b'G0ld3n_Tr4nsmut4t10n'

Okay, cool. Now this is used later in the disassembly:

LOAD_GLOBAL 21 (NULL + ARC4)

LOAD_FAST 2 (current_user)

CALL 1

STORE_FAST 5 (arc4_decipher)

LOAD_FAST 5 (arc4_decipher)

LOAD_ATTR 23 (NULL|self + decrypt)

LOAD_FAST 1 (ENCRYPTED_CHIMERA_FORMULA)

CALL 1

LOAD_ATTR 25 (NULL|self + decode)

CALL 0

STORE_FAST 6 (decrypted_formula)

Solution

Cool, so we just have to decrypt the formula with this key we’ve just gotten using ARC4.

>>> import arc4

>>> a = arc4.ARC4(b'G0ld3n_Tr4nsmut4t10n')

>>> a.decrypt(b'r2b-\r\x9e\xf2\x1fp\x185\x82\xcf\xfc\x90\x14\xf1O\xad#]\xf3\xe2\xc0L\xd0\xc1e\x0c\xea\xec\xae\x11b\xa7\x8c\xaa!\xa1\x9d\xc2\x90')

b'[email protected]'

3 - pretty_devilish_file

Effective Solve Time: 10 Minutes

Realtime Solve Time: 3 Hours

Here we get a PDF file and no real further instructions. Fun! I can’t seem to open it in Firefox nor Adobe Acrobat, but Chromium plays nice at least.

|

|---|

| Fig: Flare-On! |

Let’s open it in a text-editor to see what we’re working with. Here, I’ve extracted the most relevant sections of the file:

...

4 0 obj

<</Length 320/Filter /FlateDecode>>stream

[unrenderable bytes]

endstream

...

7 0 obj

<</Filter /Standard/V 5/R 6/Length 256/P -1/EncryptMetadata true/CF <</StdCF <</AuthEvent /DocOpen/CFM /AESV3/Length 32>>>>/StrF /StdCF/StmF /StdCF/U ([unrenderable bytes])/O ([unrenderable bytes])/UE ([unrenderable bytes])/OE ([unrenderable bytes])/Perms ([unrenderable bytes])>>

trailer <<

/Root 2 0 R

/#52#6F#6F#74 1

% /Size 15

0

R

/Encrypt 7 0 R

>>

There’s honestly a bunch of shit wrong with this PDF, including but not limited to:

- Missing XREF Table

- Root is defined to be Obj 1 (

/#52#6F#6F#74 1) even though the content is actually in Obj 2 - Control sequences being commented out

But the main thing to notice is that we have an encrypted file, but somehow we’re able to view it when dropped into Chromium. Better yet, if you even so much as sneeze on this file (even something as minor as adding then deleting a character), we are then hit with the password prompt for the file.

|

|---|

| Fig: Kena |

That’s odd! It’s weird behaviour. Maybe there’s a default password being passed in? A bit of Googling tells us that there’s a User password and an Owner password, and if that user password is empty, PDF viewers can just display them. I wanted to dig into this a bit more, so here’s a quick look at the modern PDF encryption specification.

ISO 32000-2: Electric Boogaloo (or, the PDF 2.0 Specification)

I didn’t immediately land on the empty password idea. It seemed a little silly (and it irked me that it didn’t seem to work on Firefox…) so I thought maybe other parts of the PDF fuckery were to blame and decided to give ISO 32000-2 a good read to make sure there weren’t any caveats with this PDF encryption. We see AESV3 in the EncryptMetadata section, so let’s look at that part.

…

(PDF 2.0) The security handler defines the use of encryption and decryption in the document, using the rules specified by the CF, StmF, StrF and EFF entries using 7.6.3.2, “Algorithm 1.A: Encryption of data using the AES algorithms” with a file encryption key length of 256 bits.

…

7.6.3.2 Algorithm 1.A: Encryption of data using the AES algorithms

Use the 32-byte file encryption key for the AES-256 symmetric key algorithm, along with the string or stream data to be encrypted. Use the AES algorithm in Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) mode, which requires an initialization vector.

The block size parameter is set to 16 bytes, and the initialization vector is a 16-byte random number that is stored as the first 16 bytes of the encrypted stream or string.

The output is the encrypted data to be stored in the PDF file.

Okay, so now we know what the encryption method is. How is this 32 byte key derived? Here are the snippets most relevant to us from the spec:

7.6.4.3.2 Algorithm 2.A: Retrieving the file encryption key from an encrypted document in order to decrypt it (revision 6 and later)

To understand the algorithm below, it is necessary to treat the 48-bytes of the O and U strings in the Encrypt dictionary as made up of three sections, as described in Algorithms 8 and 9. The first 32 bytes are a hash value (explained below). The next 8 bytes are called the Validation Salt. The final 8 bytes are called the Key Salt. Whenever UTF-8 password is used below, steps (a) and (b) are to be applied to the relevant password string to generate the UTF-8 password.

…

e) Compute an intermediate user key by computing a hash using algorithm 2.B with an input string consisting of the UTF-8 user password concatenated with the 8 bytes of user Key Salt. The 32-byte result is the key used to decrypt the 32-byte UE string using AES-256 in CBC mode with no padding and an initialization vector of zero. The 32-byte result is the file encryption key.

It really doesn’t seem like there’s a way to fuck with this derivation (Algorithm 2.B implementation not shown because it’s long as hell and not particularly relevant, its just multiple rounds of AES-128 over a SHA-256 hash). There is an interesting note in the specification, however!

Okay awesomesauce. Let’s look for some existing implementation of PDF AESV3 decryption and just whack with an empty string for a password. Obviously, there’s already a Python library that exists called pypdf which supports the latest PDF 2.0 encryption spec. So let’s just whack that, yeah?

>>> from pypdf import PdfReader, PdfWriter

>>> reader = PdfReader("pretty_devilish_file.pdf")

EOF marker not found

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<python-input-1>", line 1, in <module>

reader = PdfReader("pretty_devilish_file.pdf")

File ".venv/lib/python3.13/site-packages/pypdf/_reader.py", line 131, in __init__

self._initialize_stream(stream)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~^^^^^^^^

File ".venv/lib/python3.13/site-packages/pypdf/_reader.py", line 153, in _initialize_stream

self.read(stream)

~~~~~~~~~^^^^^^^^

File ".venv/lib/python3.13/site-packages/pypdf/_reader.py", line 592, in read

self._find_eof_marker(stream)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~^^^^^^^^

File ".venv/lib/python3.13/site-packages/pypdf/_reader.py", line 698, in _find_eof_marker

line = read_previous_line(stream)

File ".venv/lib/python3.13/site-packages/pypdf/_utils.py", line 316, in read_previous_line

raise PdfStreamError(STREAM_TRUNCATED_PREMATURELY)

pypdf.errors.PdfStreamError: Stream has ended unexpectedly

Solution

Oi. Well, since we so intimately know the spec now, why don’t we just do the decryption ourselves? Looking at the source of pypdf, we can find the function verify_user_password, which implements Algorithm 6 and Algorithm 2.A from the specification. This also helps us verify that the user password is in fact just, well, blank.

1import pypdf

2

3f = open("pretty_devilish_file.pdf", "rb")

4f.seek(0x498+15)

5U = (f.read(2+48))[1:-1]

6f.seek(3, 1)

7O = ((f.read(2+48)))[1:-1]

8f.seek(4, 1)

9UE = (f.read(2+32))[1:-1]

10f.seek(4, 1)

11OE = (f.read(2+33))[1:-1] # eh why the fuck is this 33 bytes

12f.seek(7, 1)

13Perms = (f.read(2+16))[1:-1]

14a = pypdf._encryption.AlgV5()

15key = a.verify_user_password(6, b'', U, UE)

16assert key != b''

Ok, it checks out. Let’s decrypt the FlateDecode stream with AES, following the previously mentioned spec:

1f.seek(0x240+5) # get to the stream

2data = f.read(320)

3print(data[:16])

4print(data[16:])

5

6from Crypto.Cipher import AES

7import zlib

8cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv=data[:16])

9pdf_section = (zlib.decompress(cipher.decrypt(data[16:])))

10

11print(pdf_section.decode())

This gives us:

q 612 0 0 10 0 -10 cm

BI /W 37/H 1/CS/G/BPC 8/L 458/F[

/AHx

/DCT

]ID

ffd8ffe000104a46494600010100000100010000ffdb00430001010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101ffc0000b080001002501011100ffc40017000100030000000000000000000000000006040708ffc400241000000209050100000000000000000000000702050608353776b6b7030436747577ffda0008010100003f00c54d3401dcbbfb9c38db8a7dd265a2159e9d945a086407383aabd52e5034c274e57179ef3bcdfca50f0af80aff00e986c64568c7ffd9

EI Q

q

BT

/ 140 Tf

10 10 Td

(Flare-On!)'

ET

Q

The DCT string is short for Discrete Cosine Transform, which is a dead giveaway that we’ve got a JPEG stream here. Let’s view the image!

1import io

2from PIL import Image

3

4start_marker = b"ID\n"

5end_marker = b"\nEI"

6

7start_index = pdf_section.find(start_marker) + len(start_marker)

8end_index = pdf_section.find(end_marker)

9hex_image_data = pdf_section[start_index:end_index]

10

11image_bytes = bytes.fromhex(hex_image_data.decode('ascii'))

12image = Image.open(io.BytesIO(image_bytes))

13image.show()

|

|---|

| Fig: what… |

Well, turns out it’s a 1x32 image. How silly. Since its greyscale its probably just encoding ASCII values or something, so we do a simple for i in range(32): print(chr(image.getpixel((i, 0))), end = "") and get our flag!

Flag: Puzzl1ng-D3vilish-F0rmat@flare-on

4 - UnholyDragon

Effective Solve Time: 2 Minutes??

Realtime Solve Time: 3.5 Hours

UnholyDragon was a really silly challenge. We’re given an EXE file, UnholyDragon-150.exe, and running it, we get…

|

|---|

| Fig: Aw man |

Initial Analysis

Ok, what’s wrong with this EXE? Let’s toss it into our favourite PE file analysis tool, PE-bear (massive shoutout to hasherezade by the way, just putting it out there) we get…

|

|---|

| Fig: Aw man! |

Maybe we’re not dealing with a PE file?? Let’s do a quick hexdump to check.

$ xxd UnholyDragon-150.exe | head

00000000: 155a 0000 0200 0000 0400 0f00 ffff 0000 .Z..............

00000010: b800 0000 0000 0000 4000 1a00 0000 0000 ........@.......

00000020: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000030: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 e800 0000 ................

00000040: ba10 000e 1fb4 09cd 21b8 014c cd21 9090 ........!..L.!..

00000050: 5468 6973 2070 726f 6772 616d 206d 7573 This program mus

00000060: 7420 6265 2072 756e 2075 6e64 6572 2057 t be run under W

00000070: 696e 646f 7773 0d0a 2437 0000 0000 0000 indows..$7......

00000080: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000090: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

Oh. The file magic is just broken. Let’s fix up the first byte and run the EXE.

Interesting! So it generates another 4 binaries that, uh, don’t run. Let’s toss this into Ghidra to see what we’re actually dealing with.

Decompilation

The program is actually written in Visual Basic and compiled with twinBASIC (twin, twin, compile me twin). There aren’t any nice decompilers around for this, so we just work with the pseudo-C we can get from Ghidra, which is more than sufficient.

Wafting through the code, we find the main program logic resides at 0x04a8f30.

We first spot some simple operations that seem to piece together the filepath of the executable.

1 iVar6 = FUN_004a53a0();

2 if ((iVar6 < 0) ||

3 (HVar7 = VarBstrCat(apOStackY_2dc[iVar2 + 1],(BSTR)&u_\_004b08cc,apOStackY_2dc + iVar2),

4 HVar7 < 0)) goto die;

5 pbstrResult = (LPBSTR)apOStackY_2dc[iVar2];

6 iVar6 = FUN_004a3cd8();

7 if ((iVar6 < 0) ||

8 (HVar7 = VarBstrCat(aOStackY_2e0 + iVar2 * 2,apOStackY_2dc[iVar2 + 2],pbstrResult), HVar7 < 0))

9 goto die;

10 HVar7 = VarBstrCat(apOStackY_2dc[iVar2 + 1],u_.exe_004b08d4,apOStackY_2dc + iVar2);

11 pOVar9 = apOStack_220[3];

This is easily verifiable via debugging.

|

|---|

Fig: Breaking after the last VarBstrCat and observing the stack |

Skimming a bit more, we find what seems to be the construction of a new string, which happens to be the next file in sequence.

1 HVar7 = VarBstrFromI4((LONG)apOStack_220[4],0x409,0,apOStack_248 + iVar2 * 2 + 0xfffffffb)

2 ;

3 if (-1 < HVar7) {

4 HVar7 = VarBstrCat(u_UnholyDragon-_004b093c,apOStack_248[iVar2 * 2 + 0xfffffffb],

5 apOStack_248 + iVar2 * 2 + -6);

6 if (-1 < HVar7) {

7 ppOStackY_274 = (BSTR *)0x4a95f0;

8 HVar7 = VarBstrCat(apOStack_248[iVar2 * 2 + -6],u_.exe_004b095c,

9 apOStack_248 + iVar2 * 2 + -7);

10 pOVar9 = apOStack_220[5];

11 if (-1 < HVar7) {

12 pOVar20 = apOStack_248[iVar2 * 2 + -7];

13 LOCK();

14 apOStack_220[5] = (BSTR)0x0;

15 UNLOCK();

16 if (pOVar9 != (BSTR)0x0) {

17 SysFreeString(pOVar9);

18 }

If it wasn’t patently obvious already, the next file produced is dependent on the iteration number of the current executable. Neat! So what happens if we change the filename to UnholyDragon-0.exe?

We kena blasted. More executables spawn and run themselves until we hit UnholyDragon-150.exe, whereby the application fails to open due to the invalid magic. Hold on, the invalid magic is back? How?

Program Behaviour

Let’s actually finish analysing the decomp. A lot of the functions are kinda like wrappers around KERNEL32 functions, e.g.

1undefined4 FUN_004a5de7(short param_1,DWORD *param_2)

2

3{

4 DWORD lDistanceToMove;

5 DWORD DVar1;

6 int iVar2;

7

8 if ((ushort)(param_1 - 1U) < 0x200) {

9 iVar2 = param_1 * 0x54 + DAT_004b09a4;

10 if (*(HANDLE *)(iVar2 + -0x54) != (HANDLE)0xffffffff) {

11 lDistanceToMove = SetFilePointer(*(HANDLE *)(iVar2 + -0x54),0,(PLONG)0x0,1);

12 DVar1 = SetFilePointer(*(HANDLE *)(iVar2 + -0x54),0,(PLONG)0x0,2);

13 *param_2 = DVar1;

14 SetFilePointer(*(HANDLE *)(iVar2 + -0x54),lDistanceToMove,(PLONG)0x0,0);

15 return 0;

16 }

17 }

18 return 0x80004005;

19}

Like, that’s just a wrapper around SetFilePointer. Since it’d be a bit annoying to showcase all of these wrappers, in brief what the program does is:

- Makes a copy of the current file

UnholyDragon-n.exe - Goes to a file offset depending on the current iteration

- Changes a byte in accordance to the iteration count

- Writes this modified copy to

UnholyDragon-{n+1}.exe - Call

CreateProcessWon the new modified copy

We can verify this behaviour just by comparing any two consecutive binaries to see that there’s only a single byte difference.

$ diff <(xxd ./UnholyDragon-123.exe) <(xxd ./UnholyDragon-124.exe) --color

156563c156563

< 00263920: d986 b878 684c 8f12 3ab5 88ad 5962 74a7 ...xhL..:...Ybt.

---

> 00263920: d986 b878 680e 8f12 3ab5 88ad 5962 74a7 ...xh...:...Ybt.

But honestly, we didn’t even have to figure all this out.

Solution

The solution is kinda goofy. We know that the chain of copying and executing halts at UnholyDragon-150.exe because it overwrites the first byte, breaking the file magic. What if we start from Iteration 0, generate all the way until Iteration 150, fix the magic, and carry on?

Flag: [email protected]

Oh. Huh. It took me a while to actually arrive at this because I got hung up over the challenge description, thinking I had to find, like, the least corrupt binary amongst these 150 or something. It didn’t help that when analysing the program logic, I didn’t actually think much about how many possible changed/corrupted bytes there are? Honestly, in retrospect, I have no clue why this took so long to solve.

5 - ntfsm

Effective Solve Time: 5 Hours

Realtime Solve Time: Half a day

Now this is a fun one! We’re presented with a console based flagchecker, which demands a 16 character input. Giving some bogus input leads to a bunch of console windows flashing and an ominous message box that repeats for a few clicks:

|

|---|

| Fig: Erm, hi. |

The challenge name is interesting. Maybe it’s a combination of NTFS (NT Filesystem) and FSM (Finite State Machine)? This is called foreshadowing.

Initial Analysis

Our main function resides at FUN_14000c0b0, and there’s immediately some reference to an FSM off the bat.

1 thunk_FUN_140ff1700(local_110,"state"); // <-- string assignment

2 thunk_FUN_140ff1700(local_e8,"input");

3 thunk_FUN_140ff1700(local_c0,"position");

4 thunk_FUN_140ff1700(local_98,"transitions");

5 local_8e8 = 0;

6 local_8e0 = 0;

7 local_8d8 = local_480;

8 local_8d0 = thunk_FUN_140ff1640(local_8d8,local_c0); // <-- string copying

9 local_8c8 = local_8d0;

10 thunk_FUN_140ff0fe0(local_8d0,&local_8e8);

11 local_8c0 = local_458;

12 local_8b8 = thunk_FUN_140ff1640(local_8c0,local_98);

13 local_8b0 = local_8b8;

14 thunk_FUN_140ff0fe0(local_8b8,&local_8e0);

Looking at our decompilation, it doesn’t take much effort to identify some of the functions, even if we don’t have symbols. FUN_140ff1700 appears to be a string assignment function, FUN_140ff1640 appears to be a string copy function. FUN_140ff0fe0 is of interest, however:

1void FUN_140ff0fe0(undefined8 param_1,LPVOID param_2)

2

3{

4 undefined8 uVar1;

5 LPCSTR lpFileName;

6 HANDLE hFile;

7 undefined1 auStackY_c8 [32];

8 undefined1 local_60 [40];

9 undefined1 local_38 [40];

10 ulonglong local_10;

11

12 local_10 = DAT_14132c040 ^ (ulonglong)auStackY_c8;

13 uVar1 = thunk_FUN_140ff1640(local_60,param_1);

14 thunk_FUN_14000acb0(local_38,uVar1);

15 lpFileName = (LPCSTR)thunk_FUN_140ff44f0(local_38);

16 hFile = CreateFileA(lpFileName,0x80000000,0,(LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES)0x0,3,0x80,(HANDLE)0x0);

17 if (hFile == (HANDLE)0xffffffffffffffff) {

18 ~basic_string<>(local_38);

19 ~basic_string<>(param_1);

20 }

21 else {

22 ReadFile(hFile,param_2,8,(LPDWORD)0x0,(LPOVERLAPPED)0x0);

23 CloseHandle(hFile);

24 ~basic_string<>(local_38);

25 ~basic_string<>(param_1);

26 }

27 thunk_FUN_140ff6530(local_10 ^ (ulonglong)auStackY_c8);

28 return;

29}

Here we find a call to CreateFileA with the fifth flag, dwCreationDisposition, set to 3, or OPEN_EXISTING, so we’re opening an existing file here. What file are we reading here? We can break on the first call of this function and see what’s the value of lpFileName, which should lie in RCX.

RAX : 00000000008EDA40 "D:\\Projects\\ctfs\\flareon\\2025\\5_-_ntfsm\\ntfsm.exe:state"

RBX : 0000000000000000

RCX : 00000000008EDA40 "D:\\Projects\\ctfs\\flareon\\2025\\5_-_ntfsm\\ntfsm.exe:state"

RDX : 0000000080000000

RBP : 0000000000000000

RSP : 00000000007FFC30

RSI : 0000000000000000

RDI : 0000000000000000

R8 : 0000000000000000

R9 : 0000000000000000

R10 : 00000000008D0000

R11 : 00000000007FF4F0

R12 : 0000000000000000

R13 : 0000000000000000

R14 : 0000000000000000

R15 : 0000000000000000

RIP : 0000000140FF1075 ntfsm.0000000140FF1075

RFLAGS : 0000000000000344 L'̈́'

...

Hey, it’s the filename of the executable with… :state appended. You can do that?

NTFS Quirks: Alternate Data Streams

TL;DR: You can add extra data streams onto files in NTFS, and we read/write to it in this challenge. That’s it. Keep reading this section if you want an unnecessarily in-depth exploration.

To quote the Microsoft documentation:

All files on an NTFS volume consist of at least one stream - the main stream – this is the normal, viewable file in which data is stored. The full name of a stream is of the form below.

<filename>:<stream name>:<stream type>

The default data stream has no name. That is, the fully qualified name for the default stream for a file called "sample.txt" is "sample.txt::$DATA" since "sample.txt" is the name of the file and "$DATA" is the stream type.

A user can create a named stream in a file and "$DATA" as a legal name. That means that for this stream, the full name is sample.txt:$DATA:$DATA. If the user had created a named stream of name "bar", its full name would be sample.txt:bar:$DATA. Any legal characters for a file name are legal for the stream name (including spaces)

So we appear to be reading data from an alternate data stream (ADS) tied to this executable. Albeit obvious, we are also writing to the ADS at other points in the program, and this is how the state of the FSM is being maintained for this challenge.

ADS is a quirk specific to NTFS (of course) which was apparently implemented to enable compatibility with the Mac Hierarchical File System (HFS). Basically, in HFS, files were stored with two forks, one for data (the actual program data) and one for resources (metadata, icons, etc.).

|

|---|

| Fig: A handy diagram from Chapter 1 of Inside Macintosh |

A Windows file server would thus use ADS to store the resource fork and keep the program data in the default unnamed data stream to maintain compatability. This shit has been around since Windows NT 3.1 (which was when NTFS was introduced, if the name didn’t make it obvious) and has stuck around since. To the surprise of absolutely nobody, ADS is actively used by malware developers and APTs (see: TA397 Payload Smuggling), with the first virus known to have abused it dating back to September, 2000 with W2K/Stream, written by members of everyone’s favourite VXer collective 29A (there’s a short piece by Symantec on it in the Virus Bulletin, dated October 2000).

Actually, how the fuck are these streams even implemented?

The Master File Table

NTFS contains a file called the master file table (MFT). To quote the docs:

All information about a file, including its size, time and date stamps, permissions, and data content, is stored either in MFT entries, or in space outside the MFT that is described by MFT entries.

Every file record in the MFT is 1024 bytes large and it contains pointers to where the data actually is on the volume (depending on how much additional info needs to be stored, the file record can either be Resident i.e. within the MFT or Non-Resident i.e. in an external cluster). In truth, NTFS treats files as a set of attributes (relevant doc), which are all stored as separate streams. Here are some examples:

$STANDARD_INFORMATION

Standard information, such as file times and quota data

Always resident, contains key metadata

╔════╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╗

║ ║ 0 ║ 1 ║ 2 ║ 3 ║ 4 ║ 5 ║ 6 ║ 7 ║ 8 ║ 9 ║ A ║ B ║ C ║ D ║ E ║ F ║

╠════╬═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╬═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╣

║ 0 ║ Date Created ║ Date Modified ║

╠════╬═══════════════════════════════╬═══════════════════════════════╣

║ 10 ║ Date MFT record modified ║ Date Accessed ║

╠════╬═══════════════╦═══════════════╬═══════════════╦═══════════════╣

║ 20 ║ Flags ║ Max Versions ║ Version Num ║ Class ID ║

╠════╬═══════════════╬═══════════════╬═══════════════╩═══════════════╣

║ 30 ║ Owner ID ║ Security ID ║ Quota Charged ║

╠════╬═══════════════╩═══════════════╬═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╣

║ 40 ║ Update Sequence Number ║ ║ ║ ║ ║ ║ ║ ║ ║

╚════╩═══════════════════════════════╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╝

$FILE_NAME

More metadata!

╔════╦══════════╦═══════════╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╦═══╗

║ ║ 0 ║ 1 ║ 2 ║ 3 ║ 4 ║ 5 ║ 6 ║ 7 ║ 8 ║ 9 ║ A ║ B ║ C ║ D ║ E ║ F ║

╠════╬══════════╩═══════════╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╬═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╩═══╣

║ 0 ║ Parent Directory ║ Date Created ║

╠════╬══════════════════════════════════════════════╬═══════════════════════════════╣

║ 10 ║ Date Modified ║ Date MFT Modified ║

╠════╬══════════════════════════════════════════════╬═══════════════════════════════╣

║ 20 ║ Date Accessed ║ Logical file size ║

╠════╬══════════════════════════════════════════════╬═══════════════╦═══════════════╣

║ 30 ║ Size on disk ║ Flags ║ Reparse value ║

╠════╬══════════╦═══════════╦═══════════════════════╩═══════════════╩═══════════════╣

║ 40 ║ Name len ║ Name type ║ Name ║

╚════╩══════════╩═══════════╩═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════╝

In fact, if a file is small enough, the file data can be entirely resident within the $DATA attribute (900 bytes or smaller, apparently)!

Anyways, as we’ve established, you can have multiple data streams, which in turn means multiple $DATA attributes attached to one file record. The creation of an ADS is essentially the creation of a new ATTRIBUTE_RECORD of TypeCode == 0x80 and a given name. In the case of our challenge, it is most definitely a resident attribute record due to how tiny the data we’re storing is.

Unsurprisingly, there is a limit to how many ADSs you can tack onto a file, which is a hard limit of 0x40000. Here’s a nifty blogpost on that topic (TL;DR: If you have many attributes, an $ATTRIBUTE_LIST attribute is used as a pointer table, which has a size cap of 256kb. Since ADSs must be named, these names will quickly exhaust said size cap).

Knowing how ADSs work is wholly irrelevant to actually solving the challenge, but I think it’s still a fun thing to look at. For posterity, here’s how you view the ADSs in Powershell.

PS D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm> Get-Item -Path ntfsm.exe -Stream *

PSPath : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm\ntfsm.exe::$DATA

PSParentPath : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm

PSChildName : ntfsm.exe::$DATA

PSDrive : D

PSProvider : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem

PSIsContainer : False

FileName : D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm\ntfsm.exe

Stream : :$DATA

Length : 20151296

PSPath : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm\ntfsm.exe:input

PSParentPath : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm

PSChildName : ntfsm.exe:input

PSDrive : D

PSProvider : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem

PSIsContainer : False

FileName : D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm\ntfsm.exe

Stream : input

Length : 16

PSPath : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm\ntfsm.exe:position

PSParentPath : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm

PSChildName : ntfsm.exe:position

PSDrive : D

PSProvider : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem

PSIsContainer : False

FileName : D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm\ntfsm.exe

Stream : position

Length : 8

PSPath : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm\ntfsm.exe:state

PSParentPath : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm

PSChildName : ntfsm.exe:state

PSDrive : D

PSProvider : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem

PSIsContainer : False

FileName : D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm\ntfsm.exe

Stream : state

Length : 8

PSPath : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm\ntfsm.exe:transitions

PSParentPath : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm

PSChildName : ntfsm.exe:transitions

PSDrive : D

PSProvider : Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem

PSIsContainer : False

FileName : D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm\ntfsm.exe

Stream : transitions

Length : 8

Back to the Actual Challenge

Okay, cool. We’re reading from an ADS. Let’s clean up the first bit of the decompilation now to see what our win condition is:

1 string_assign(s_state,"state");

2 string_assign(s_input,"input");

3 string_assign(s_position,"position");

4 string_assign(s_transitions,"transitions");

5 n = 0;

6 k = 0;

7 local_8d8 = local_480;

8 s_position_copy = string_copy(local_8d8,s_position);

9 local_8c8 = s_position_copy;

10 read_ads(s_position_copy,&n);

11 local_8c0 = local_458;

12 s_transitions_copy = string_copy(local_8c0,s_transitions);

13 local_8b0 = s_transitions_copy;

14 read_ads(s_transitions_copy,&k);

15 if (n == 16) {

16 if (k == 16) {

17 printf("correct!\n");

18 puVar4 = local_30;

19 for (i = 0x11; i != 0; i = i + -1) {

20 *puVar4 = 0;

21 puVar4 = puVar4 + 1;

22 }

23 local_8a8 = local_430;

24 local_8a0 = string_copy(local_8a8,s_input);

25 local_898 = local_8a0;

26 cVar1 = readfile_2(local_8a0,local_30,0x10);

27 if (cVar1 != '\0') {

28 assign_string(local_70,local_30);

29 thunk_FUN_14000b2a0(local_70);

30 ~basic_string<>(local_70);

31 }

32 ... // truncated

33 /* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

34 exit(0);

35 }

36 printf("wrong!\n");

37 ... // truncated

38 /* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

39 exit(1);

40 }

So we need our position to be 16 and our transitions to be 16 as well.

Upon input of our 16 byte password, we first initialise all the ADSs to be 0.

1 strcpy(inp_arg,*(undefined8 *)(argv + 8));

2 local_6f8 = local_1d8;

3 s_copy_input = string_copy(local_6f8,s_input);

4 local_6e8 = s_copy_input;

5 write_ads(s_copy_input,inp_arg,16);

6 local_6e0 = local_1b0;

7 s_position_copy_1 = string_copy(local_6e0,s_position);

8 local_6d0 = s_position_copy_1;

9 write_ads_1(s_position_copy_1,0);

10 local_6c8 = local_188;

11 s_transitions_copy_1 = string_copy(local_6c8,s_transitions);

12 local_6b8 = s_transitions_copy_1;

13 write_ads_1(s_transitions_copy_1,0);

14 local_6b0 = local_160;

15 s_state_copy_1 = string_copy(local_6b0,s_state);

16 local_6a0 = s_state_copy_1;

17 write_ads_1(s_state_copy_1,0);

And this is followed up by a mysterious jump…

1 s_state_copy = string_copy(local_790,s_state);

2 local_780 = s_state_copy;

3 read_ads(s_state_copy,&state_val);

4 ...

5 s_input_copy_2 = string_copy(local_698,s_input);

6 local_688 = s_input_copy_2;

7 read_ads_1(s_input_copy_2,inp_arg,0x10);

8 uStack_59368 = inp_arg[n];

9 local_680 = 0;

10 local_678 = 0;

11 local_670 = 0;

12 local_668 = 0;

13 if (state_val == 0xffffffffffffffff) {

14 state_val = 0;

15 }

16 local_660 = state_val;

17 if (state_val < 0x1629d) {

18 /* WARNING: Could not recover jumptable at 0x00014000ca5a. Too many branches */

19 /* WARNING: Treating indirect jump as call */

20 (*(code *)(IMAGE_DOS_HEADER_140000000.e_magic + *(uint *)(&DAT_140c687b8 + state_val * 4)))

21 (IMAGE_DOS_HEADER_140000000.e_magic + *(uint *)(&DAT_140c687b8 + state_val * 4));

22 return;

23 }

The point of focus here is DAT_140c687b8. Just by looking at the pseudocode, we can tell that this is somehow behaving like a function table, with the state_val behaving as our indexer! Let’s actually resolve this address (we can get the address dynamically while debugging on the side, too) and look at the next block of pseudocode after the jump (with the symbols filled in).

1void UndefinedFunction_140860241(void)

2{

3 ulonglong uVar1;

4 undefined8 in_RAX;

5 ulonglong uVar2;

6 undefined8 uVar3;

7 ulonglong uVar4;

8 char current_char;

9 ulonglong in_stack_00059380;

10 undefined8 *in_stack_000593a8;

11 longlong position;

12 longlong state;

13 longlong transition;

14

15 uVar4 = rdtsc();

16 uVar2 = CONCAT44((int)((ulonglong)in_RAX >> 0x20),(int)uVar4) | uVar4 & 0xffffffff00000000;

17 uVar4 = uVar2;

18 do {

19 uVar1 = rdtsc();

20 uVar4 = (CONCAT44((int)(uVar4 >> 0x20),(int)uVar1) | uVar1 & 0xffffffff00000000) - uVar2;

21 } while ((longlong)uVar4 < 0x12ad1659);

22 if (current_char == 'J') {

23 state = 2;

24 transition = transition + 1;

25 }

26 else if (current_char == 'U') {

27 state = 3;

28 transition = transition + 1;

29 }

30 else if (current_char == 'i') {

31 state = 1;

32 transition = transition + 1;

33 }

34 else {

35 ShellExecuteA((HWND)0x0,"open","cmd.exe"," /c msg * Hello there, Hacker",(LPCSTR)0x0,5);

36 }

37

38 uVar3 = string_copy(&stack0x00058ef0,&stack0x000592d8);

39 write_ads_1(uVar3,position + 1);

40 uVar3 = string_copy(&stack0x00058f90,&stack0x00059300);

41 write_ads_1(uVar3,transition);

42 if (state != 0) {

43 uVar3 = string_copy(&stack0x000590d0,&stack0x00059288);

44 write_ads_1(uVar3,state);

45 }

46 thunk_FUN_14000b050(*in_stack_000593a8);

47 ~basic_string<>(&stack0x00059300);

48 ~basic_string<>(&stack0x000592d8);

49 ~basic_string<>(&stack0x000592b0);

50 ~basic_string<>(&stack0x00059288);

51 thunk_FUN_140ff6530(in_stack_00059380 ^ (ulonglong)&stack0x00000000);

52 return;

53}

Nice! We see some actual flagchecking logic here. The current_char is just plucked off the stack from earlier and following a series of checks, we determine what the next state should be. The last important bit is FUN_14000b050, which at a glance is a call to CreateProcessA on the binary itself.

1void FUN_14000b050(LPSTR param_1)

2

3{

4 longlong lVar1;

5 _STARTUPINFOA *p_Var2;

6 _PROCESS_INFORMATION *p_Var3;

7 _PROCESS_INFORMATION local_98;

8 _STARTUPINFOA local_78;

9

10 p_Var2 = &local_78;

11 for (lVar1 = 0x68; lVar1 != 0; lVar1 = lVar1 + -1) {

12 *(undefined1 *)&p_Var2->cb = 0;

13 p_Var2 = (_STARTUPINFOA *)((longlong)&p_Var2->cb + 1);

14 }

15 local_78.cb = 0x68;

16 p_Var3 = &local_98;

17 for (lVar1 = 0x18; lVar1 != 0; lVar1 = lVar1 + -1) {

18 *(undefined1 *)&p_Var3->hProcess = 0;

19 p_Var3 = (_PROCESS_INFORMATION *)((longlong)&p_Var3->hProcess + 1);

20 }

21 CreateProcessA((LPCSTR)0x0,param_1,(LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES)0x0,(LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES)0x0,1,0,

22 (LPVOID)0x0,(LPCSTR)0x0,&local_78,&local_98);

23 WaitForSingleObject(local_98.hProcess,0xffffffff);

24 return;

25}

The new spawned process will have the updated state value from the previous position and we carry on as such…

Debugging this does become a bitch due to the fact that a new process is spawned, and during the CTF itself I used DbgChild to automatically attach x64dbg to the new process so I could continue tracing the logic just a little more to verify my assumptions. However, that isn’t really necessary as we more or less have a full view of the program logic already:

- Start with your intial input, intialize your state, position and transition to 0

- Based on your state, jump to the appropriate function in the function table

- Function table will act on the character pointed to by position, update state and transition accordingly

- Spawn a child process with the updated state, incremented position, then repeat steps 2–4 until position reaches 16

- Win when we follow a pathway that produces a transition of 16

Solution

The character checking functions are all quite stereotyped, where each character CMP is associated with a new state value, from which we can derive the next set of possible checking functions.

In more precise terms, each checking function has a block like this:

MOV byte ptr [RSP + 0x4c],AL

CMP byte ptr [RSP + 0x4c],0x44

JE LAB_14000ce72

CMP byte ptr [RSP + 0x4c],0x55

JE LAB_14000ce51

CMP byte ptr [RSP + 0x4c],0x78

JE LAB_14000ce93

And each of the blocks that you jump to looks like this:

MOV qword ptr [RSP + 0x58d30],0x403b

MOV RAX,qword ptr [RSP + 0x58ab8]

INC RAX

MOV qword ptr [RSP + 0x58ab8],RAX

Where the MOV into [RSP + 0x58d30] is our new state. This is consistent! So we can come up with a simple capstone script to parse this:

1va = base_address + current_offset

2rva = va - pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.ImageBase

3

4code = pe.get_data(rva, 300)

5md = Cs(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64)

6md.detail = True

7instructions = list(md.disasm(code, va))

8new_block = False

9for i in range(len(instructions) - 1):

10 instr = instructions[i]

11 next_instr = instructions[i + 1]

12 if instr.mnemonic == "cmp":

13 if next_instr.mnemonic == "je":

14 jmp = next_instr.operands[0].imm

15 # get the block in jumps to here

16 print(f"Found JE at 0x{next_instr.address:x} targeting 0x{jmp:x}")

17

18 # disasm that shit

19 target_rva = jmp - pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.ImageBase

20 target_code = pe.get_data(target_rva, 50)

21 target_instructions = list(md.disasm(target_code, jmp))

22

23 for target_instr in target_instructions:

24 # find our state change value

25 if target_instr.mnemonic == "mov" and "qword ptr [rsp + 0x58d30]" in target_instr.op_str:

26 n = target_instr.operands[1].imm

27 cmp = instr.operands[1].imm

28 print(f"Found MOV at 0x{target_instr.address:x} with n = {n}")

29 print(f"Corresponding CMP value: {cmp}")

30 break

31 else:

32 # we just fuck off if we don't find any more CMPs followed by JMPs

33 if new_block: break

34 new_block = True

And now we can essentially create a gigantic graph of all the possible states and their next possible paths, taking note of which character at which position gets you where. Our goal is to find a path of length 16, so we just BFS that until we find a solution.

1import pefile

2from capstone import *

3import struct

4import sys

5from collections import deque

6

7BINARY_PATH = "./ntfsm.exe"

8BINARY_BASE = 0x140000000

9OFFSETS_ARRAY_BASE_RVA = 0xc687b8

10

11def r_uint32(pe, base_rva, i):

12 offset_rva = base_rva + (i * 4)

13 data = pe.get_data(offset_rva, 4)

14 return struct.unpack("<I", data)[0]

15

16def bfs(pe, base_address, initial_offset, offsets_base_rva):

17 queue = deque([(initial_offset, 0, 0, [])])

18 while queue:

19 current_offset, cur_len, n_val, cur_path = queue.popleft()

20 if cur_len == 16:

21 print(f"Path taken (CMP values): {cur_path}")

22 return

23

24 va = base_address + current_offset

25 rva = va - pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.ImageBase

26 code = pe.get_data(rva, 300)

27 md = Cs(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64)

28 md.detail = True

29 instructions = list(md.disasm(code, va))

30 new_block = False

31 for i in range(len(instructions) - 1):

32 instr = instructions[i]

33 next_instr = instructions[i + 1]

34 if instr.mnemonic == "cmp":

35 if next_instr.mnemonic == "je":

36 jmp = next_instr.operands[0].imm

37 target_rva = jmp - pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.ImageBase

38 target_code = pe.get_data(target_rva, 50)

39 target_instructions = list(md.disasm(target_code, jmp))

40

41 for target_instr in target_instructions:

42 if target_instr.mnemonic == "mov" and "qword ptr [rsp + 0x58d30]" in target_instr.op_str:

43 n = target_instr.operands[1].imm

44 cmp = instr.operands[1].imm

45 new_path = cur_path + [cmp]

46 next_offset = r_uint32(pe, offsets_base_rva, n)

47 if next_offset is not None:

48 queue.append((next_offset, cur_len + 1, n, new_path))

49 break

50 else:

51 if new_block: break

52 new_block = True

53

54def main():

55 pe = pefile.PE(BINARY_PATH)

56 initial_offset = r_uint32(pe, OFFSETS_ARRAY_BASE_RVA, 0)

57 bfs(pe, BINARY_BASE, initial_offset, OFFSETS_ARRAY_BASE_RVA)

58

59if __name__ == "__main__":

60 main()

This script takes quite a while to run, but we eventually hit our singular 16 length path: iqg0nSeCHnOMPm2Q

Tossing this into the binary, we get our flag!

PS D:\Projects\ctfs\flareon\2025\5_-_ntfsm> .\ntfsm.exe iqg0nSeCHnOMPm2Q

correct!

Your reward: [email protected]

6 - Chain of Demands

For this challenge, we’re given an ELF file! What a pleasant surprise. Running it, we’re presented with a Tkinter ass looking interface and a few debug logs in our console.

|

|---|

| Fig: Look ma, a GUI. |

[SETUP] - Generated Seed 561393684898852237728015324140376177975

[SETUP] Generating LCG parameters from system artifact...

[SETUP] - Found parameter 1: 10199765946783533694...

[SETUP] - Found parameter 2: 99472079278540720821...

[SETUP] - Found parameter 3: 11395549359680152905...

[!] Connection error: [!] Failed to connect to Ethereum network a

Please check your RPC_URL and network connection.

[SETUP] LCG Oracle is on-chain...

[!] Connection error: [!] Failed to connect to Ethereum network a

Please check your RPC_URL and network connection.

[SETUP] Triple XOR Oracle is on-chain...

[SETUP] Crypto backend initialized...

We’ve got some Web3 shenanigans it seems. Clicking the “Last Convo” button, we get some extra details:

|

|---|

| Fig: How convenient! |

A public key, chat logs talking about RSA encryption… looks like we have an idea as to what we wanna do for this challenge, at least. Clicking the “Web3 Config” button, we see a prompt for an RPC URL and Private Key.

|

|---|

| Fig: The “Web3 Config” prompt |

Let’s get anvil running and pass those in.

This is followed up by a whole bunch of logs:

[+] Connected to Sepolia network at http://127.0.0.1:8545

[+] Current block number: 0

[+] Using account: 0xf39Fd6e51aad88F6F4ce6aB8827279cffFb92266

[+] Account balance: 10000 ETH

[+] Estimated gas for deployment: 211970

[+] Current gas price: 2 Gwei

[+] Deploying contract...

[+] Deployment transaction sent. Hash: b617924fb29748da2da141936f8d9a1b31e6c29e499f9f81052243f48ec9fdcd

[+] Waiting for transaction to be mined...

[+] Transaction receipt: AttributeDict({'type': 0, 'status': 1, 'cumulativeGasUsed': 211970, 'logs': [], 'logsBloom': HexBytes('0x000...'), 'transactionHash': HexBytes('0xb617924fb29748da2da141936f8d9a1b31e6c29e499f9f81052243f48ec9fdcd'), 'transactionIndex': 0, 'blockHash': HexBytes('0x5c73be3b4151bfdf7bac66babcd3f0d5759fd3556c45ba32b1b2dc086775b5d0'), 'blockNumber': 1, 'gasUsed': 211970, 'effectiveGasPrice': 2000000000, 'blobGasPrice': 1, 'from': '0xf39Fd6e51aad88F6F4ce6aB8827279cffFb92266', 'to': None, 'contractAddress': '0x5FbDB2315678afecb367f032d93F642f64180aa3'})

[+] Contract deployed at address: 0x5FbDB2315678afecb367f032d93F642f64180aa3

[SETUP] LCG Oracle is on-chain...

[+] Connected to Sepolia network at http://127.0.0.1:8545

[+] Current block number: 1

[+] Using account: 0xf39Fd6e51aad88F6F4ce6aB8827279cffFb92266

[+] Account balance: 9999.99957606 ETH

[+] Estimated gas for deployment: 222439

[+] Current gas price: 1.876766417 Gwei

[+] Deploying contract...

[+] Deployment transaction sent. Hash: b07dcb7bd53f38fc8d283e8e0d33595bd93ea3604c3ace62477be6504d626d42

[+] Waiting for transaction to be mined...

[+] Transaction receipt: AttributeDict({'type': 0, 'status': 1, 'cumulativeGasUsed': 222439, 'logs': [], 'logsBloom': HexBytes('0x000...'), 'transactionHash': HexBytes('0xb07dcb7bd53f38fc8d283e8e0d33595bd93ea3604c3ace62477be6504d626d42'), 'transactionIndex': 0, 'blockHash': HexBytes('0xbb9d8905ea3dce87df5b6e81c7ebe9db5920416ef7c073ed203ac8765c97905c'), 'blockNumber': 2, 'gasUsed': 222439, 'effectiveGasPrice': 1876766417, 'blobGasPrice': 1, 'from': '0xf39Fd6e51aad88F6F4ce6aB8827279cffFb92266', 'to': None, 'contractAddress': '0xe7f1725E7734CE288F8367e1Bb143E90bb3F0512'})

[+] Contract deployed at address: 0xe7f1725E7734CE288F8367e1Bb143E90bb3F0512

[SETUP] Triple XOR Oracle is on-chain...

[SETUP] Crypto backend initialized...

So we’ve got some contracts being deployed? We can now press connect and screw around with the program, which produces, like, hella logs. We can see our RSA key being generated when we click “Enable Super-Safe Encryption”, we can see calls to an LCG, and it’s implied the less secure encryption mode is some sort of LCG-XOR encryption.

|

|---|

| Fig: Sending some secure messages. |

[+] Calling encrypt() with prime_from_lcg=112215942746702486312289645599652166193775789330547223149621746105218527606662, time=148, plaintext=a

_ciphertext = 9917f90a699dca385810de4de1515315630ed343783fd86262d3eb915b1b3712

Initial Analysis

Now that we have a feel for how the program works, we can get to actually reversing. Closing the program with SIGINT makes our next step obvious:

^CTraceback (most recent call last):

File "challenge_to_compile.py", line 480, in <module>

File "tkinter/__init__.py", line 1508, in mainloop

KeyboardInterrupt

[PYI-2551:ERROR] Failed to execute script 'challenge_to_compile'

due to unhandled exception!

So we’re dealing with compiled and bundled Python. Nice!

Decompilation

We grab ourselves a copy of pyinstxtractor so we can get ahold of challenge_to_compile.pyc.

|

|---|

| Fig: Me when the py is instxtractor’d |

Tossing that into pycdc, we get a mostly complete recovery of the original source, though we still combine this with a simple dis diassembly to make up for some of the incomplete decompilation.

Let’s go function by function…

1def _initialize_crypto_backend(self):

2 self.seed_hash = self._get_system_artifact_hash()

3 (m, c, n) = self._generate_primes_from_hash(self.seed_hash)

4 self.lcg_oracle = LCGOracle(m, c, n, self.seed_hash)

5 self.lcg_oracle.deploy_lcg_contract()

6 print('[SETUP] LCG Oracle is on-chain...')

7 self.xor_oracle = TripleXOROracle()

8 self.xor_oracle.deploy_triple_xor_contract()

9 print('[SETUP] Triple XOR Oracle is on-chain...')

10 print('[SETUP] Crypto backend initialized...')

Let’s take a look at those first two functions, eh:

1def _get_system_artifact_hash(self):

2 artifact = platform.node().encode('utf-8') # no way for us to get this

3 hash_val = hashlib.sha256(artifact).digest()

4 seed_hash = int.from_bytes(hash_val, 'little')

5 print(f'''[SETUP] - Generated Seed {seed_hash}...''')

6 return seed_hash

7

8def _generate_primes_from_hash(self, seed_hash):

9 primes = []

10 current_hash_byte_length = (seed_hash.bit_length() + 7) // 8

11 current_hash = seed_hash.to_bytes(current_hash_byte_length, 'little')

12 print('[SETUP] Generating LCG parameters from system artifact...')

13 iteration_limit = 10000

14 iterations = 0

15 if len(primes) < 3 and iterations < iteration_limit:

16 current_hash = hashlib.sha256(current_hash).digest()

17 candidate = int.from_bytes(current_hash, 'little')

18 iterations += 1

19 if candidate.bit_length() == 256 and isPrime(candidate):

20 primes.append(candidate)

21 print(f'''[SETUP] - Found parameter {len(primes)}: {str(candidate)[:20]}...''')

22 if len(primes) < 3 and iterations < iteration_limit:

23 continue

24 if len(primes) < 3:

25 error_msg = '[!] Error: Could not find 3 primes within iteration limit.'

26 print('Current Primes: ', primes)

27 print(error_msg)

28 exit()

29 return (primes[0], primes[1], primes[2])

So three 256-bit prime numbers are generated using a SHA256 hash that we can’t obtain. That’s okay though, because we see that these numbers are used as the initialization parameters for LCGOracle, so maybe we can extract it from here?

1class LCGOracle:

2

3 def __init__(self, multiplier, increment, modulus, initial_seed):

4 self.multiplier = multiplier

5 self.increment = increment

6 self.modulus = modulus

7 self.state = initial_seed

8 self.contract_bytes = '60806040...' # truncated for aesthetic reasons

9 self.contract_abi = [

10 {

11 'inputs': [

12 {

13 'internalType': 'uint256',

14 'name': 'LCG_MULTIPLIER',

15 'type': 'uint256' },

16 {

17 'internalType': 'uint256',

18 'name': 'LCG_INCREMENT',

19 'type': 'uint256' },

20 {

21 'internalType': 'uint256',

22 'name': 'LCG_MODULUS',

23 'type': 'uint256' },

24 {

25 'internalType': 'uint256',

26 'name': '_currentState',

27 'type': 'uint256' },

28 {

29 'internalType': 'uint256',

30 'name': '_counter',

31 'type': 'uint256' }],

32 'name': 'nextVal',

33 'outputs': [

34 {

35 'internalType': 'uint256',

36 'name': '',

37 'type': 'uint256' }],

38 'stateMutability': 'pure',

39 'type': 'function' }]

40 self.deployed_contract = None

41

42

43 def deploy_lcg_contract(self):

44 self.deployed_contract = SmartContracts.deploy_contract(self.contract_bytes, self.contract_abi)

45

46

47 def get_next(self, counter):

48 print(f'''\n[+] Calling nextVal() with _currentState={self.state}''')

49 self.state = self.deployed_contract.functions.nextVal(self.multiplier, self.increment, self.modulus, self.state, counter).call()

50 print(f''' _counter = {counter}: Result = {self.state}''')

51 return self.state

We deploy a contract with its raw bytecode and thankfully, we’ve got some descriptive argument names as well. It seems like we really are just initializing a 256-bit LCG. Tossing the raw bytecode into an EVM Decompiler, we don’t get particularly nice output:

1contract Contract {

2 function main() {

3 memory[0x40:0x60] = 0x80;

4 var var0 = msg.value;

5

6 if (var0) { revert(memory[0x00:0x00]); }

7

8 if (msg.data.length < 0x04) { revert(memory[0x00:0x00]); }

9

10 var0 = msg.data[0x00:0x20] >> 0xe0;

11

12 if (var0 != 0x11521834) { revert(memory[0x00:0x00]); }

13

14 var var1 = 0x0047;

15 var var2 = 0x0042;

16 var var4 = 0x04;

17 var var3 = var4 + (msg.data.length - var4);

18 var var5;

19 var var6;

20 var2, var3, var4, var5, var6 = func_010C(var3, var4);

21 var var7 = 0x00;

22 var var8 = 0x00;

23 var var9 = var4;

24

25 if (var9) {

26 var var10 = var3;

27 var var11 = var4;

28

29 if (var11) {

30 var var12 = var2;

31 var var13 = var5;

32 // Unhandled termination

33 } else {

34 var12 = 0x007d;

35

36 label_01AB:

37 memory[0x00:0x20] = 0x4e487b7100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000;

38 memory[0x04:0x24] = 0x12;

39 revert(memory[0x00:0x24]);

40 }

41 } else {

42 var10 = 0x006d;

43 goto label_01AB;

44 }

45 }

46

47 function func_00D9(var arg0) returns (var r0) { return arg0; }

48

49 function func_00E2(var arg0) {

50 var var0 = 0x00eb;

51 var var1 = arg0;

52 var0 = func_00D9(var1);

53

54 if (arg0 == var0) { return; }

55 else { revert(memory[0x00:0x00]); }

56 }

57

58 function func_00F8(var arg0, var arg1) returns (var r0) {

59 var var0 = msg.data[arg1:arg1 + 0x20];

60 var var1 = 0x0106;

61 var var2 = var0;

62 func_00E2(var2);

63 return var0;

64 }

65

66 function func_010C(var arg0, var arg1) returns (var r0, var arg0, var arg1, var r3, var r4) {

67 r3 = 0x00;

68 r4 = 0x00;

69 var var2 = 0x00;

70 var var3 = 0x00;

71 var var4 = 0x00;

72

73 if (arg0 - arg1 i>= 0xa0) {

74 var var5 = 0x00;

75 var var6 = 0x0132;

76 var var7 = arg0;

77 var var8 = arg1 + var5;

78 var6 = func_00F8(var7, var8);

79 r3 = var6;

80 var5 = 0x20;

81 var6 = 0x0143;

82 var7 = arg0;

83 var8 = arg1 + var5;

84 var6 = func_00F8(var7, var8);

85 r4 = var6;

86 var5 = 0x40;

87 var6 = 0x0154;

88 var7 = arg0;

89 var8 = arg1 + var5;

90 var6 = func_00F8(var7, var8);

91 var2 = var6;

92 var5 = 0x60;

93 var6 = 0x0165;

94 var7 = arg0;

95 var8 = arg1 + var5;

96 var6 = func_00F8(var7, var8);

97 var3 = var6;

98 var5 = 0x80;

99 var6 = 0x0176;

100 var7 = arg0;

101 var8 = arg1 + var5;

102 var6 = func_00F8(var7, var8);

103 var temp0 = r4;

104 r4 = var6;

105 arg0 = temp0;

106 var temp1 = r3;

107 r3 = var3;

108 r0 = temp1;

109 arg1 = var2;

110 return r0, arg0, arg1, r3, r4;

111 } else {

112 var5 = 0x0124;

113 revert(memory[0x00:0x00]);

114 }

115 }

116}

Honestly, I can’t be arsed to look at the disassembly and statically solve this. We’ve got an ABI, we’ve got the locally generated constants, we can just interact with the contract and see if the behaviour checks out.

$ cast call 0x5FbDB2315678afecb367f032d93F642f64180aa3 "nextVal(uint256, uint256, uint256, uint256, uint256)(uint256)" 10199765946783533694 99472079278540720821 11395549359680152905 561393684898852237728015324140376177975 0

561393684898852237728015324140376177975 [5.613e38]

$ cast call 0x5FbDB2315678afecb367f032d93F642f64180aa3 "nextVal(uint256, uint256, uint256, uint256, uint256)(uint256)" 10199765946783533694 99472079278540720821 11395549359680152905 561393684898852237728015324140376177975 1

5424462414644024856 [5.424e18]

$ cast call 0x5FbDB2315678afecb367f032d93F642f64180aa3 "nextVal(uint256, uint256, uint256, uint256, uint256)(uint256)" 10199765946783533694 99472079278540720821 11395549359680152905 5424462414644024856 2

11246440529847084330 [1.124e19]

$ cast call 0x5FbDB2315678afecb367f032d93F642f64180aa3 "nextVal(uint256, uint256, uint256, uint256, uint256)(uint256)" 10199765946783533694 99472079278540720821 11395549359680152905 11246440529847084330 2

5675029262062990626 [5.675e18]

$ cast call 0x5FbDB2315678afecb367f032d93F642f64180aa3 "nextVal(uint256, uint256, uint256, uint256, uint256)(uint256)" 10199765946783533694 99472079278540720821 11395549359680152905 11246440529847084330 3

5675029262062990626 [5.675e18]

Testing a few numbers we see that the LCG formula of $a_{k+1} \equiv m\times a_k + c \pmod{n}$ holds up.

Similarly, we can test the TripleXOROracle contract dynamically, and, well:

$ cast call 0xe7f1725E7734CE288F8367e1Bb143E90bb3F0512 "encrypt(uint256, uint256, string)(bytes32)" 0 0 "sphinxofblackquartz"

0x737068696e786f66626c61636b71756172747a00000000000000000000000000

$ cast call 0xe7f1725E7734CE288F8367e1Bb143E90bb3F0512 "encrypt(uint256, uint256, string)(bytes32)" 123456 0 "sphinxofblackquartz"

0x737068696e786f66626c61636b71756172747a0000000000000000000001e240

$ cast call 0xe7f1725E7734CE288F8367e1Bb143E90bb3F0512 "encrypt(uint256, uint256, string)(bytes32)" 123456 98765 "sphinxofblackquartz"

0x737068696e786f66626c61636b71756172747a0000000000000000000000638d

Just by eyeballing, we can see that it really is just XORing the three values passed in together (0x638d = 123456 ^ 98765,

0x737068696e786f66626c61636b71756172747a == sphinxofblackquartz), with the text being padded to fill the MSB. We can verify this just by sending messages on our local instance:

[+] Calling encrypt() with prime_from_lcg=14647903786015167264287355746212153578894037287044524203041946738598968382923, time=6, plaintext=testing2

_ciphertext = 5407180044141ba03878467fa99f2ea84f7846ae0c4d153095e27a37e28d55cd

# now we can just calculate the triple XOR

0x20626b742d7a7c923878467fa99f2ea84f7846ae0c4d153095e27a37e28d55cb ^ 6 ^ (b'testing2' + b'\00'*24) == 0x5407180044141ba03878467fa99f2ea84f7846ae0c4d153095e27a37e28d55cd

Great! Our solve path is now relatively clear:

- From the LCG-XOR portion of the chat log, recover the LCG values

- From the recovered LCG values, somehow recover the LCG paramters

- Run the LCG to recover the prime factorisation of N for RSA

- Trivially break RSA

Breaking an LCG

Let’s do a little crypto. To reiterate, an LCG is defined as

$$ a_{k+1} \equiv m\times a_k + c \pmod{n} $$

Where $m$ is our multiplier, $c$ is our constant, $n$ is our modulus and we have some initialisation value $a_0$. In this challenge, we’re able to recover 7 (seven) values from our LCG by undoing the Triple Baka XOR “Encryption”:

1import json

2

3states = []

4logs = json.load(open("chat_log.json"))

5for i in range(7):

6 c = (logs[i]["conversation_time"]).to_bytes(32)

7 pt = (logs[i]["plaintext"]).encode()

8 pt += b'\00'*(32-len(pt))

9 ct = bytes.fromhex(logs[i]['ciphertext'])

10 states.append(int.from_bytes(bytes([c[n] ^ pt[n] ^ ct[n] for n in range(32)])))

With no other information, how do we retrieve the initial values? Thankfully, we’re not the first person to have asked this question, and there is a nice, comprehensive blogpost on this topic already. I’d like to go through the math in brief still, though!

Step 1: Recovering the Modulus

This relies on a simple rearrangement of terms to produce an expression that is a multiple of $n$, then solving for the greatest common divisor of a few of these expressions.

The construction is as such: $$ a_{k+1} \equiv m\times a_k + c \pmod{n} \\ \text{Let} \;\; b_{k+1} = a_{k+2}-a_{k+1} \\ \equiv (m\times a_{k+1} + c) - (m\times a_k + c) \\ \equiv m(a_{k+1}-a_k) \equiv m\times b_k \pmod{n} \\ \implies b_{k+2} b_{k} - b_{k+1} b_{k+1} \\ \equiv mb_{k+1} \times b_k - b_{k+1} b_{k+1} \\ \equiv b_{k+1} \times m b_k - b_{k+1}b_{k+1} \\ \equiv b_{k+1} b_{k+1} - b_{k+1} b_{k+1} \equiv 0 \pmod{n} \\ \therefore b_{k+2} b_{k} - b_{k+1} b_{k+1} = xn $$

We can thus construct multiple such $b_{k+2} b_{k} - b_{k+1} b_{k+1}$ to produce several values which will have $n$ as a common divisor (and with high probability of being the gcd).

1def get_modulus(states):

2 b = [a1 - a0 for a0, a1 in zip(states, states[1:])]

3 vals = [b2*b0 - b1*b1 for b0, b1, b2 in zip(b, b[1:], b[2:])]

4 n = abs(gcd(vals))

5 return n

Step 2: Recovering the Multiplier

With our existing construction, this is fairly direct!

$$ b_{k+1} \equiv m\times b_k \pmod{n} \implies b_{k+1} b_k^{-1} \equiv m \pmod{n} $$

This is also a simple implementation:

1def get_multiplier(states, n):

2 m = (states[2] - states[1]) * inverse_mod(states[1] - states[0], n)

3 m %= n

4 return m

Step 3: Recovering the Constant

And this is the simplest to recover of the bunch. By definition, $a_{k+1} \equiv m\times a_k + c \pmod{n} \implies a_{k+1} - m\times a_k \equiv c \pmod{n}$.

1def get_constant(states, n, m):

2 return (states[1] - states[0] * m) % n

All Together Now

Let’s put this altogether and see what values we get!

--- Recovered Values ---

Recovered Modulus: 98931271253110664660254761255117471820360598758511684442313187065390755933409

Recovered Multiplier: 11352347617227399966276728996677942514782456048827240690093985172111341259890

Recovered Constant: 61077733451871028544335625522563534065222147972493076369037987394712960199707

This does perturb me a little because these are all meant to be prime values derived from a SHA256 hash, so how can we have an even multiplier? This bothered me for a grand total of 2 (two) minutes before I decided to cringe on and see what happens.

We get our initial seed easily by taking the first LCG output and computing $(a_1 - c) m^{-1} \pmod{n}$, giving us 80631529052001100272845413254760303954872303349693249834992925889079643767931.

Solution

Let’s get our RSA modulus first from the public key file.

1>>> from Crypto.PublicKey import RSA

2>>> key = RSA.import_key(open("public.pem", "rb").read())

3>>> key.n

4966937097264573110291784941768218419842912477944108020986104301819288091060794069566383434848927824136504758249488793818136949609024508201274193993592647664605167873625565993538947116786672017490835007254958179800254950175363547964901595712823487867396044588955498965634987478506533221719372965647518750091013794771623552680465087840964283333991984752785689973571490428494964532158115459786807928334870321963119069917206505787030170514779392407953156221948773236670005656855810322260623193397479565769347040107022055166737425082196480805591909580137453890567586730244300524109754079060045173072482324926779581706647

Now, we rederive the modulus by running our LCG, keeping track of the primes along the way.

1candidate = 80631529052001100272845413254760303954872303349693249834992925889079643767931

2m = 11352347617227399966276728996677942514782456048827240690093985172111341259890

3n = 98931271253110664660254761255117471820360598758511684442313187065390755933409

4c = 61077733451871028544335625522563534065222147972493076369037987394712960199707

5

6rsa_n = 966937097264573110291... # truncated for aesthetic reasons

7primes = []

8

9for i in range(10000):

10 candidate = (candidate*m + c) % n

11 if candidate.bit_length() == 256 and isPrime(candidate):

12 if rsa_n % candidate == 0:

13 primes.append(candidate)

14 rsa_n //= candidate

In spite of our initial LCG parameters not all being prime as expected, we still manage to derive the correct RSA modulus, so uh. Fucking whatever.

Now we can trivially break RSA by calculating the totient value $\Phi(n)$ and deriving our decryption exponent!

1t = 1

2for p in primes: t *= (p-1)

3e = 65537

4d = pow(e, -1, t)

5

6import json

7logs = json.load(open("chat_log.json"))

8

9ct = bytes_to_long(bytes.fromhex(logs[7]["ciphertext"])[::-1])

10print(long_to_bytes(pow(ct, d, rsa_n)))

11ct = bytes_to_long(bytes.fromhex(logs[8]["ciphertext"])[::-1])

12print(long_to_bytes(pow(ct, d, rsa_n)))

13

14# b"Actually what's your email?"

15# b"It's [email protected]"

Flag: [email protected]

Alternate Solution

Here’s an alt solution I saw on twitter dot com:

|

|---|

| Fig: #Yup |

Honestly, unsurprising. This was an odd difficulty drop all things considered, especially when compared to the next three challenges…

Closing Remarks

These first 6 (six) challenges weren’t particularly tough and they were cleared pretty quickly! I managed to get these done (with interruptions) over 3.5 days which gave me a lot more buffer time to tackle the significantly harder challenges 7 through 9 over the remaining duration of FLARE-On.

Stay tuned for Part 2 where I fail to write deobfuscation scripts in Ghidra and completely forget elementary abstract algebra!